Solon in Egypt: The priests show him

the Atlantis story on papyri (Bing AI)

Christian Vassallo studied Classics and is currently Professor of Papyrology at the University of Turin in Italy. In recent years, he has published two articles on the topics of Plato, history and Atlantis, to which we would like to take a closer look at here:

The article on Plato's understanding of history is very analytical and focusses on details. This approach leads to quite good results: Vassallo elaborates on various aspects of Plato's views on history.

Vassallo correctly observed that people are not thrown back to zero after every catastrophe, but retain certain memories and techniques that can become the "seeds" of a new cultural development, such as the techniques of pottery and weaving (The Laws III 679a).

However, Vassallo is too optimistic about the transmission of historical knowledge and political techniques. He is also imprecise in his thinking: for example, he formulates the concept of a "collective 'unconscious' memory" (p. 192), i.e., a memory that only lies dormant in the unconscious. This is particularly difficult to imagine for the transmission of historical events and political techniques, and it also seems to be a modern projection to attribute such an idea to Plato.

It is also problematic that Vassallo apparently sees the role of conveying information on these topics precisely in myths. Plato criticised traditional myths because they often conveyed false information. It seems to be the case that philosophical, myth-critical thinking first has to develop from scratch. In Plato's story of Atlantis, for example, it is said that only the names of earlier generations have survived: This does not mean that the names of famous people were still remembered, but that the mere names themselves were preserved by giving these names to children and grandchildren. Only the names means: Not much information.

This is where another of Vassallo's errors comes into play: According to the Atlantis story, he says: "Plato doubtless considered it the only way to avoid forgetting 'historical' events through written philosophical myths, as recorded in his dialogues, rather than through primitive, oral myths." (p. 186) – This is correct so far, but one thing is wrong: for Plato, the written tradition from Egypt was no longer mythos but logos, because the written history of Atlantis is set against the merely orally transmitted myths of the Greeks as a tradition of better quality. Vassallo's concept of "written philosophical myths" is therefore completely unplatonic. Likewise, he repeatedly calls the Atlantis story "mythical" (e.g. p. 184). For Plato, the Atlantis story from Egypt was precisely not a mythos and also not "historical" but historical.

Vassallo is absolutely right that there is a certain Hellenocentrism in Plato. This is also generally recognised. However, in this context Vassallo puts forward a thesis that goes too far: "Extra Graeca nulla historia" (pp. 193-195). This means that Plato only considered a historical development for Greek cities, while he did not recognise any historical development for "barbarian" peoples.

But this is wrong. Unlike Vassallo, we see the principle of Interpretatio Graeca, the recognition of Greek deities in foreign deities, not as an exclusive but as an inclusive principle. In this way, foreign cultures were not marginalised but incorporated.

Then there is the example of Egypt: Egypt is a non-Greek country, but it does have a history, indeed, and unlike Greece, it has historical records. Of course, the history of Egypt in the eyes of the Greeks consisted precisely in the fact that not much changed in this country, but insofar as Sais is interpreted by Plato as a degenerated ideal state, and insofar as Egypt must also emerge anew in every great cosmic cycle (Platonic Myth in Politicus), Egypt is also subject to historical development.

Atlantis is also a non-Greek state with a history, even if it is of course not a success story.

Finally, reference should be made to a statement in Plato's Politeia, according to which the ideal state can also explicitly emerge in a distant, non-Greek country. This makes it quite clear that Vassallo's thesis is not tenable:

"If then, in the countless ages of the past, or at the present hour in some foreign clime which is far away and beyond our ken, the perfected philosopher is or has been or hereafter shall be compelled by a superior power to have the charge of the State, we are ready to assert to the death, that this our constitution has been, and is –yea, and will be whenever the Muse of Philosophy is queen."

(Republic VI 499cd; translation Benjamin Jowett)

Vassallo does not bring his individual observations together to form a big overall picture. It is possible to integrate all phenomena into one big picture, in which mythos and logos are interwoven as Plato saw it:

The reason why Vassallo did not create this integrated picture probably lies in a misunderstanding of Plato's philosophy. Although a scientific mythos is uncertain, it nevertheless conveys a more or less probable knowledge. And some of the stories that are "only" mythos in Vassallo's eyes are even logos in Plato's eyes. It is important to understand how seriously, directly and historically Plato meant all this.

Vassallo obviously sees it differently. This becomes clear from the fact that Vassallo puts quotation marks around words such as "history", as if Plato had only meant these facts ironically or in a figurative sense "historically". But this is not the case. It becomes even clearer where Vassallo wants to interpret Plato's gods as an "ethical model" (p. 189). This is a completely unplatonic interpretation that imposes a modern view on Plato.

Nevertheless, Vassallo's detailed analyses in this article are of lasting value. On the whole, this is a good article. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the following article. A final conclusion to both articles follows below.

The errors that were already apparent in Vassallo's article on Plato's understanding of history now come to full fruition in this article. Yet the main reason why this article is a complete disaster is that Vassallo relies on the prevailing errors of the invention hypothesis, and here especially on the theses of Alan Cameron and Harold Tarrant, which are wrong and fragile in many ways. This is not Christian Vassallo's fault.

Specifically, it is about the correct interpretation of the famous passage in Proclus, which deals with Crantor and Plato's Atlantis. Vassallo uses the term "fr. 8 Mette" for this passage. Our own translation reads:

"Some say that the story [logos] about everything connected with the Atlantines would be pure history [historia psile], as (e.g.) Plato's first commentator Crantor. This [Crantor] now says, that he [Plato] was mocked by the contemporaries, since he was not the creator of (his) constitution, but (only) the transcriber of (the constitution) of the Egyptians. He [Plato] cared so much about this (countering) word of the mockers, that he [Plato] traced back the story [historia] about the Athenians and Atlantines to the Egyptians, that the Athenians once lived according to this constitution. The priests of the Egyptians [prophetai] attest this, says he [Crantor!], by saying that this is written on still existing stelai."

(Proclus In Timaeum 24A f. or I 1,75 f.; translation Thorwald C. Franke)

The article suffers from a multitude of formal problems, which alone are enough to completely undermine any scientific statement. As in the first article, words are repeatedly placed in quotation marks so that it is not entirely clear whether they are meant seriously or not, for example in the statement non fossero fantasiose invenzioni ma fatti "storici" (p. 419). How can "facts", which are understood as the opposite of "fantastic inventions", not be historical but only "historical" in quotation marks? The reader is at a loss. – Already in the abstract there is a formulation that is contradictory in itself: "we may guess it surely ruled out" (p. 405). How can something be a "guess" and "surely" at the same time? The conclusion is analogous: "but to me it seems sufficiently certain" ("ma mi sembra abbastanza certo", p. 422). How can it only "seem" and at the same time be "certain"?

The word "sembrare" ("seem") appears seventeen times throughout the text. For example, in "the Neoplatonists seem to have attested" ("i Neoplatonici sembrano attestarsi", p. 406), "Proclus seems to have had no disagreement with" ("Proclo non sembra essere in disaccordo con", p. 408), "Aristotle seems" ("Aristotele sembra", p. 408), "do not seem decisive to me" ("non mi sembrano decisive", p. 420), or "but it seems sufficiently certain to me" ("ma mi sembra abbastanza certo", p. 422).

Several times the author uses his personal conviction because no clear argument is at hand, e.g. in "personally I think" ("personalmente, penso", p. 414) or "I think that" ("penso che", p. 417), "I am convinced that" ("sono convinto che", p. 420), or "in my judgement" ("a mio giudizio", p. 421). In principle, a scientific author may also express his personal opinion, but only in passing, otherwise the investigation ceases to be a rational argument and becomes merely subjective.

The author himself repeatedly has to admit that his own reasoning is dubious: "does not resolve all the doubts raised" ("non risolvono tutti i dubbi sollevati", p. 416), or "how this solution raises further doubts" ("come tale soluzione sollevi ulteriori dubbi", p. 418). – The phrase "d'altro canto" is repeatedly interspersed (pp. 414, 418, 420), which expresses an "on the other hand" without the various alternatives being weighed up conclusively against each other.

In at least two places we find a strange rabulism: although Alan Cameron's argumentation is explicitly recognised as weak, it is nevertheless upheld because quite a few considerations are linked to the conclusion that Alan Cameron's arguments hit the mark ("dopo non pochi ripensamenti sono giunto alla conclusione che gli argomenti di Cameron, nonostante i punti deboli, colgano nel segno", p. 420). But that cannot be an argument! – It is said, because a Greek in Egypt certainly could not read hieroglyphics, it is ultimately irrelevant on a theoretical level whether Crantor or Plato is the subject of the last sentence of the Proclus passage, because in the end it boils down to the Egyptian priests as the originators of the statement (p. 420). But unfortunately it is not that simple; it makes a considerable difference whether Crantor or Plato is the subject of the sentence.

Proclus' point of view on the Atlantis question is initially worked out correctly over several pages and confirmed several times (406-412): Proclus interprets the Atlantis story on two levels simultaneously: according to Plato, the Atlantis story is "true in every respect" (Timaeus 20d), and thus on both a symbolic and a real level. Atlantis is therefore also real for Proclus, but not only. This is entirely in line with the traditional interpretation and can be accepted. Truth would therefore unfold on two levels: symbolic and real (p. 410). So far so good.

But a few pages later, with a brief reference to "above", it is suddenly claimed that Proclus only meant a symbolic truth in the Atlantis story ("Ovviamente, come osservato sopra, la difesa di Proclo della "storicità" di Atlantide non implica che egli accetti il termine historia secondo il nostro concetto di "storia".", p. 415). There is no recognisable argumentation as to why it should be as claimed. For "above" there is no explanation for what is claimed here. The fact that this statement is introduced with "Obviously" ("Ovviamente") is highly suggestive. Nothing is obvious here.

It is said of Aristotle that he "seems" to have adopted a sceptical attitude towards the historical content of the Atlantis story, "more or less maliciously directed against Plato" ("più o meno maliziosamente diretto contro Platone", p. 408). This is nothing other than the classically false assertion made at the beginning of the 19th century by the Atlantis sceptic Delambre that Strabo's passage 2.3.6 contained a statement by Aristotle against the existence of Plato's Atlantis. This claim can now be considered refuted (cf. Franke (2012): Aristotle and Atlantis). Numerous authors have changed or tacitly dropped their arguments on this issue in recent years.

But it gets even worse! In footnote 13, these passages are briefly cited in support of this assertion: Aristot. Meteor. 2.1.354a11-23; Coel. 2.14.297b31-298a16; fr. 402 Gigon (=fr. 162 Rose). – These are the "mud passage" and the "Columbus passage" in the works of Aristotle, and Strabo 13.1.36 (Homer and the Wall of the Achaeans). However, Strabo 2.3.6, the central passage for the assertion made, is not mentioned! And no author from the secondary literature is cited to explain this argument. This makes it clear that Vassallo has not even begun to understand the problematic nature of this alleged statement by Aristotle against the existence of Plato's Atlantis.

The reception history of Plato's Atlantis story is dealt with in this sentence: "If we exclude Posidonius and, on the Platonist side, Plutarch and Longinus, we can say that the anti-historical (i.e., anti-literalist) attitude represented the predominant hermeneutical line." ("Se si escludono Posidonio e, sul versante platonico, Plutarco e Longino, possiamo dire che l'attegiamento anti-storico (i.e., anti-letteralista) abbia rappresentato la linea ermeneutica prevalente", p. 408)

That is of course far too simplistic. You cannot simply exclude this or that author and then claim that the other side prevailed. In addition, the testimony of Theophrastus pro existence is completely ignored. Strabo, who agreed with Posidonius, is also missing. Aristotle may also have been more inclined in favour of existence. And last but not least, we have the testimony of Crantor in favour of existence. All in all, the prevailing hermeneutic line was of course overwhelmingly in favour of existence. The first Atlantis sceptic known by name did not appear until 500 years after Plato: It was Numenius of Apamea.

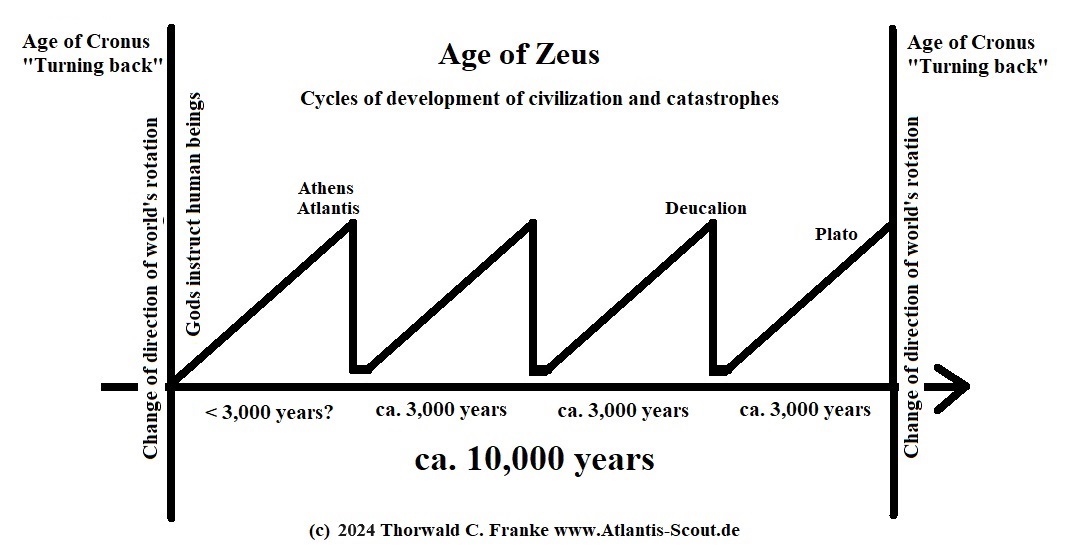

Another typical error is the characterisation of the Atlantis story as "eccentric" ("eccentrica", p. 416), and here specifically as "eccentric" in comparison to other Platonic Myths. But this is wrong. The Atlantis story contains no magic, no miracles, no monsters. There are only gods as city founders, but that is the case with every real ancient city. Elephants are also real animals. Not even the buildings and armies are larger than known buildings, because Herodotus knows of even larger buildings and armies, and of even older times. In other Platonic Myths, on the other hand, we find highly unusual things: for example, people who regress from old age to embryo (Politicus), or the afterlife journey of Er (Republic). In addition, important elements of the Atlantis story are confirmed in other dialogues, such as an age of Egypt of more than 10,000 years (a prevailing misconception at the time), or cyclical catastrophism. It is therefore simply false that the Atlantis story was unusual for Plato and therefore required special justification, as is claimed here (p. 416).

Also wrong is the assumption that the Atlantis story was only passed on orally (p. 419). Plato explicitly writes of a continuous written tradition. Only to introduce a real tradition into a fictional dialogue did Plato build the bridge of an oral tradition parallel to the written tradition. The argument that epigraphic evidence is added to merely oral evidence is therefore invalid.

The adoption of an erroneous interpretation of a fragment of Longinus by Irmgard Männlein-Robert is fatal. It concerns the passage Proclus In Timaeum I 1, 83 (fragment 54), in which Longinus is mentioned in passing alongside representatives of the invention hypothesis. However, the way Longinus is mentioned there does not in any way mean that he himself is also one of the proponents of the invention hypothesis. I explained this in great detail in my 2021 review of Männlein-Robert's work "Longin – Philologe und Philosoph – Eine Interpretation der erhaltenen Zeugnisse" (Franke (2021b)). With Männlein-Robert, Vassallo now erroneously believes that Longinus could be counted among the representatives of the invention hypothesis (p. 413). This is also surprising because Vassallo himself noted in at least two other passages in his article that Longinus was closer to the representatives of the existence hypothesis (pp. 408, 412). Vassallo should have enquired more deeply here.

Another typical error is to equate the word mythos with "invention" and "fantasy" ("invenzione", "fantasia", p. 409). A mythos can be invented, but it does not have to be. A mythos could also be completely true. In addition, the word mythos meant different things at different times, which should be differentiated.

One error that Vassallo commits in the wake of Alan Cameron is the attempt to construe Crantor's so-called "metaphorical" interpretation of the Timaeus myth as a contradiction to Crantor's literalist, direct interpretation of the Atlantis story (p. 419, also pp. 414, 422).

The background is this: in fact, a so-called "metaphorical" reading of the Timaeus myth is traditionally attributed to Crantor (cf. Zeyl (2000) p. xxi; Aristotle De caelo 279b32-280a1; Proclus in Timaeum I 1,277.8-10 or 85A; Plutarch De animae procreatione in Timaeo I or 1012). But this "metaphorical" reading is in fact about the question of whether the cosmos existed eternally or was created. The former position is called "metaphorical" because its supporters argue by comparing the description of the creation to a geometric construction: The temporal progression of the geometric construction only serves to understand the geometric fact, which in itself has no temporal progression. Of course, labelling this comparison as "metaphorical" is somewhat inappropriate, because it is an analogy. The demiurge in Plato's Timaeus is obviously an analogy. This designation as "metaphorical" does not come from the ancient sources, but was developed by the reception.

In any case, the alleged contradiction does not exist: while the Atlantis story is supposed to be a written logos, i.e., a story of high certainty, the Timaeus myth is an eikos mythos, which deals with things that are highly uncertain. It is therefore completely nonsensical to expect that Crantor treated the Atlantis story and the Timaeus myth in the same way. – Last but not least, Alan Cameron, to whom this argument of Vassallo goes back, attributes a literalist reading of the Timaeus myth to Aristotle, while at the same time believing that Aristotle thought Atlantis was an invention: How this is supposed to fit together in Aristotle, if it is not supposed to fit together in Crantor, remains completely open.

Tarrant made the correct observation that the phrase historia psile in Proclus should not simply be translated as "pure history" in our modern sense. Rather, the context makes it clear that it merely means that the story has no symbolic level of interpretation.

Vassallo takes this up, but not consistently (pp. 414, 416). On the one hand, Vassallo believes, contrary to Tarrant, that historia psile in context would refer to the real historical truth of the Atlantis story after all. On the other hand, historia psile allegedly did not denote any real truth for Crantor. But then Vassallo swings back to the line of Tarrant. The whole argument seems somewhat arbitrary.

Nesselrath's argument that the reference to the Egyptian stelae does indeed signify a real historical reference, even if historia psile does not express this sufficiently, is also missing.

Another typical error of the invention hypothesis (but also of many superficial existence hypotheses) is the view that the entire Platonic ideal state can be found in the Egyptian tradition of the Atlantis story (pp. 417 f., 419). However, this is not the case. The tradition from Egypt claimed in the dialogue only contained an approximation of the ideal state, which Critias then had to supplement to form the full ideal state. Unfortunately, Vassallo builds on this erroneous assumption and categorically rejects alternative scenarios (p. 419).

At this point, the idea that Crantor is the subject of the phesi ("he said") in the last sentence is also rejected. Vasssallo correctly recognises that the grammatical structure of the passage necessarily leads to the conclusion that Crantor must be the subject. But with the argument of "inescapable contradictions" ("ineludibili contraddizioni", p. 419), this thesis is rejected against the logic of grammar. However, these contradictions stem from false assumptions.

Here again the pernicious influence of Alan Cameron is noticeable. Heinz-Günther Nesselrath's argumentation on this topic is discussed and rejected. Vassallo is too entangled in the errors of the invention thesis to be able to comprehend the straightforward correctness of Nesselrath's argumentation.

Another typical error is the failure to recognise the fact that, according to Plato, primeval Athens and Sais developed independently of each other, because both were founded independently of each other by the goddess Athena. Instead, Vassallo follows the false trail that the later-founded city of Sais was a colony of the first-founded city of Athens. This leads him to the astonishing thesis that the Egyptians "plagiarised" their constitution from primeval Athens (pp. 417 f.). And for Vassallo, this is also Plato's answer to the accusation that he plagiarised his constitution from Egypt.

At this point, Vassallo's argumentation finally comes into skidding (pp. 417-419). On the one hand, Crantor would have considered the Atlantis story to be a genuine Egyptian tradition. On the other hand, he would have considered it to be an allegorical fairy tale and an invention. Finally, Vassallo attempts to solve the insoluble dilemma by forcibly cutting the Gordian knot and dividing the meaning of the much-discussed word psile into two parts (p. 418): A "positive" meaning and a "negative" meaning. The positive side must be attributed to Plato (an invented myth with "truth" in the figurative sense), but the negative to the Egyptians (a plagiarised story).

At this point, the reader has long since lost the plot. Here, one erroneous conclusion builds on another, and at the latest when such interpretative pirouettes as splitting the meaning of one and the same word are resorted to, all credibility is lost. Especially when Vassallo adds another twist after these quibbles (p. 418): But perhaps it was quite different, perhaps Proclus misinterpreted the entire process ... Here everything seems arbitrary and over-twisted, and a stable argument is no longer recognisable.

Vassallo does not want to follow Nesselrath's argument that the "taking to hand" of the texts (ta grammata labontes) refers to papyri (p. 421). He thinks – "in my judgement" ("a mio giudizio") – that this could also be understood in a figurative sense. Moreover, "we know" that the Egyptians "published" their sacred writings in temples. And the parallel of the Oreichalkos stele would also support this.

But no. The phrase "taking to hand" is quite clear. If it had been about temple walls, it would have been spoken of differently. It is also completely false that the Egyptians used to publish their sacred writings on temple walls. The temple walls are merely the surviving remains, while most of the papyri have been destroyed. Added to this is the propagandistic and evocative function of the temple inscriptions, which did not prevail in the same way with texts on papyrus. Finally, the passage with the Oreichalkos stele does not "support" anything; there is no recognisable parallel here.

The existence of a tradition of the Atlantis story on papyrus would severely disrupt the narrative built up in this article, because it is firmly assumed that, in addition to the oral tradition, there were only the inscriptions on the stelae or temple walls.

Finally, Vassallo repeats errors from the previous article on Plato's understanding of history (p. 419): Crantor's position would confirm that Plato's understanding of history was profoundly Hellenocentric. And that the attachment of the Platonic Academy to the polis of Athens was still strong in Crantor's time. – But neither can be read out in this way. History also happened in Egypt and Atlantis. And statements about Athens' past do not presuppose any ties to Athens in the present.

We have seen two very different articles: The first article on Plato's understanding of history is well done in its detailed investigations and is of lasting value. The second article, however, is a complete failure. What is the difference?

In the first article, Vassallo proceeded very meticulously and followed his own observations very consistently, without having to take much account of other authors. Vassallo was successful here. In the second article, however, Vassallo often relied on the existing literature by representatives of the invention hypothesis on Plato's Atlantis – and therefore inevitably failed. This literature is full of errors and contradictions.

One could say: Vassallo had no chance at all. If you look at the numerous errors he had taken as a premise, the result is not surprising. The over-twisting of the argument to the point of the strangest pirouettes shows once again where the invention hypothesis leads if you try to think it through to its logical conclusion. Vassallo is thus another victim of the poor state of scholarship on the subject of Plato's Atlantis.

Cameron (1983): Alan Cameron, Crantor and Posidonius on Atlantis, in: The Classical Quarterly CQ Vol. 33 No. 1 (1983); pp. 81-91.

Fleischer (2023): Kilian Fleischer, Crantor of Soli as an Early Witness to a Revision of the Timaeus?, in: Olga Alieva / Debra Nails / Harold Tarrant (eds.), The Making of the Platonic Corpus, Band 6 der Reihe: Contexts of Ancient and Medieval Anthropology, Brill Schöningh / Koninklijke Brill NV, Paderborn 2023; pp. 152-165.

Franke (2012): Thorwald C. Franke, Aristotle and Atlantis – What did the philosopher really think about Plato's island empire?, published by Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2016. German first edition was 2010.

Franke (2016/2021): Thorwald C. Franke, Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis – von der Antike über das Mittelalter bis zur Moderne, 2. edition in 2 volumes, published by Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2021. First edition was 2016. (About Crantor pp. 39-46, 95-99; Criticism of Alan Cameron pp. 212-219; Criticism of Harold Tarrant pp. 223-236)

Franke (2021): Thorwald C. Franke, Platonische Mythen – Was sie sind und was sie nicht sind – Von A wie Atlantis bis Z wie Zamolxis, published by Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2021.

Franke (2021b): Thorwald C. Franke, Rezension zu: Irmgard Männlein-Robert, Longin – Philologe und Philosoph – Eine Interpretation der erhaltenen Zeugnisse, Dissertation Universität Würzburg Wintersemester 1999/2000, Band 143 der Reihe: Beiträge zur Altertumskunde, Verlag K.G. Saur, München / Leipzig 2001. (German only, published in Franke (2016/2021) as appendix)

https://www.atlantis-scout.de/atlantis-maennlein-robert-longin.htm

Nesselrath (2001): Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Atlantis auf ägyptischen Stelen? Der Philosoph Krantor als Epigraphiker, in: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik ZPE No. 135 (2001); pp. 33-35.

Stephens (2016): Susan Stephens, Plato's Egyptian Republic, chapter 2 in: Ian C. Rutherford (ed.), Greco-Egyptian Interactions – Literature, Translation, and Culture, 500 BCE-300 CE, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2016; pp. 41-59.

Tarrant (2006): Harold Tarrant, Proclus – Commentary on Plato's Timaeus, Vol. 1., edited and translated by Harold Tarrant, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge / New York 2006. First publication in printed form 2007.

Vassallo (2021): Christian Vassallo, Rolling Sisyphus’ Stone Uphill? Plato’s Philosophy of History and Progress Reappraised, in: The Journal of Hellenic Studies JHS No. 141 (2021); pp. 179-196.

Vassallo (2023): Christian Vassallo, Crantore lettore del prologo del Timeo: Il fr. 8 Mette tra decostruzione ed ermeneutica, in: Hermes No. 151 (2023); pp. 405-423.

Zeyl (2000): Donald J. Zeyl, Plato – Timaeus, translated, with introduction, by Donald J. Zeyl, Hacket Publishing Company, Indianapolis / Cambridge, 2000.