Pic. 1: Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Brandenstein

With his book 'Atlantis – Größe und Untergang eines geheimnisvollen Inselreiches' (i.e. 'Atlantis – Grandeur and Downfall of a mysterious island empire') a scientist with relevant expertise has expressed his views. His well-founded conclusion: The Atlantis account is a historical tradition. Thus, Atlantis is no invention by Plato but was a real place.

Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Brandenstein (1898-1967) primarily was a linguist, who worked on ancient languages under a linguist's perspective; among them ancient Persian and ancient Greek. In this capacity he directed for more than 25 years the "Institut für vergleichende Sprachwissenschaften" (i.e. Institute for comparative linguistics) at the University of Graz in Austria.

Besides his main task as linguist Brandenstein dealt also with historical questions of ancient history which not directly were connected with his focus of research. Thus, he proved to have a wider horizon, and additionally his linguistic competences enabled him to address problems under different perspectives than other research disciplines did.

Brandenstein also addressed the question how to interpret Plato's Atlantis account and published in 1951 his work 'Atlantis – Größe und Untergang eines geheimnisvollen Inselreiches' (i.e. 'Atlantis – Grandeur and Downfall of a mysterious island empire'). Although title and cover picture may suggest otherwise, it is no lurid and popular publication but a legibly written yet sophisticated academic analysis of the Atlantis account. He concludes: Atlantis nevertheless was a real place.

From most Atlantis researchers who consider Atlantis to be a real place, Wilhelm Brandenstein distinguishes himself by being a scientist in a relevant research area: He knows ancient languages and their literature, knows of literary genres and is aware of the historical context of the Atlantis account. Even if his theses will partially be revealed as errorneous and short-circuited – one reproach will always be illegitimate: That here, a pseudo-scientist was at work.

Right at the start Brandenstein gives proof of his scientific approach: He does not precipitate head over heels with bold claims into the topic, but first inserts a dry, if not boring, chapter; in this he shows, analyzes and defines what we have to understand as the concepts of myth, legend and fairy tale. On this basis Brandenstein then tries to draw a consequent conclusion on the literary genre of the Atlantis account.

For Brandenstein the Atlantis account cannot be a myth. First, this is concluded from the definition of myth: The core of a myth is formed by an inexplicable event which by myth is explained intuitively and anthropomorphically, not rationally. But the Atlantis account is of this world and backed up with several supporting facts.

A second argument is the comparison with typical mythical accounts. Brandenstein distills a basic scheme which is underlying all of these accounts, and shows: The Atlantis account deviates in a decisive point from this basic scheme: At the end, not only the "bad guys", i.e. the Atlanteans, but also the "good guys", i.e. the primeval Athenians, are doomed.

Brandenstein also rejects the idea that the Atlantis account could be a mythical allegory. This would be an artificial myth which authors of Plato's time used to invent in order to express their ideas in an better way. In the case of Plato we talk of "Platonic Myths".

The main reason for this rejection is Brandenstein's conviction that the Atlantis account can fulfill its role in its context given by Plato only, if it is a true story. Plato's intention would be to provide a proof for the correctness of his political theories. It is this why the Atlantis account contains proof for its correctness as well as assertions for its truth which were inappropriate for the literary genre of a mythical allegory.

Brandenstein concludes that Plato's Atlantis account belongs to the literary genre of the legend (German original: "Sage"). Brandenstein defines a legend as an account with a historical core. Aspects of myths and fairy tales may be there, too, but only marginal. In addition, this legend was enriched by Solon and Plato by adding well-intended but errorneous conclusions and interpretations. More on that later.

After Brandenstein excluded the possibility that Plato's Atlantis is a fictional or mythical subject matter, he analyzes the text under the perspective that Plato must have worked with a historical tradition, and this with the intention to work as historian. Thus, further arguments are disclosed in favour of Brandenstein's thesis that the Atlantis account must be a historical tradition.

As already said, according to Brandenstein Plato tries to work as historian in order to proof his political theories. From the proofs given by Plato for the historicity of the story and his assertions for its truth, Brandenstein concludes: "By this one cannot well avoid to conclude that Plato attached great importance to find belief with his Atlantis account, and that he in no way wanted to tell inventions 'with a smiling seriousness'".

Brandenstein shows that the plot of the Atlantis account actually does not fit to Plato's intention to show the probation of his ideal state by the example of primeval Athens: Because in the end not only Atlantis but also primeval Athens fall.

Brandenstein also points out the gross mismatch of the amounts of text, Plato used for the descriptions of primeval Athens and Atlantis. Primeval Athens which actually is in focus is described much more scarcely whereas Atlantis which is unimportant in comparison, is described at epic length.

By this Brandenstein concludes that it is not an invention by Plato but rather that Plato was victim of an inappropriate subject matter. Therefore, Plato did not finish his Critias since the inconsistencies between the historical tradition and his intentions turned out to be insurmountable. If Plato had invented the account, he had invented it much better.

Another hint for a historical tradition and a historical intention of Plato is seen by Brandenstein in the fact that Plato has not supplemented the subject matter arbitrarily. Rather it is recognizable that Plato sought to orient his interpretations and conclusions at the reality, as known to him.

Examples for these conclusions and interpretations would be the descriptions of changes in the landscape of Athens or the peaceful distribution of the world among the gods. In this, Plato often was somewhat short-circuited.

Especially in the peaceful distribution of the world among the gods Brandenstein sees a well-intentioned Platonic correction of the original tradition: This is documented in case of Athens as a quarrel among the gods Athena and Poseidon; in the end Athena is victorious, but Poseidon sends earthquakes and flood to Attica as punishment. This latter strongly reminds of the Atlantis account.

By replacing the quarrel of the gods by a peaceful distribution of the world, well-intentioned on the basis of his religious views, Plato eliminated the motivation for the later downfall of primeval Athens from the story. Thus, Plato created the difficulty to motivate the downfall in an other way – in which he failed, as the unfinished Critias shows.

Another of Brandenstein's arguments is that the historicizing novel developed only long after Plato in Greek literature. Plato would have anticipated a long development and evolution of literary forms and therefore would have found no understanding with his contemporary readers, if he intended to deliver a historicizing novel with his Atlantis account. This is practically impossible.

At Plato's time historical accounts always had a certain claim for truth, everything else would have not been understood. The literary device, too, to present an invented tradition, was developed much later.

Thus, Brandenstein presented a serious and strong argument, which deserves much attention; already Spyridon Marinatos expressed this view. Nevertheless, there is a gap in this argumentation: It is questionable if it is enough to look on the historicizing novel. Plato saw himself as inventor [?] of pedagogic myths, so Brandenstein's argumentation seems to be incomplete. But maybe this gap can be bridged? Then, the Atlantis account will be recognized as historical tradition with great evidential weight.

PS 14 April 2023:

(a) As demonstrated in my book about Platonic Myths from 2021, it is an urban myth that Plato invented myths and presented them as true stories. Therefore, this possible gap in Brandenstein's argument is closed.

(b) We have to report of a small mistake Brandenstein made in his argument: Brandenstein cited Lucian as a major witness of the late development of the historical novel, which is correct (p. 41). But Brandenstein confuses why Lucian is such a witness. It is not that Lucian himself wrote such novels, applying the new literary devices, but it is that Lucian wrote with his "True Histories" a well-known parody of the new literary form, and thus became an important witness ex negativo.

Besides the time when the historicizing novel was not developed, yet, Plato was everything but a born author of novels. Brandenstein cites Wilamowitz: Plato never wrote any account, historical subject matters did not excite him, he fully ignored the historians of his people. His desire to phantasize had long-since died. It would "truly strange" if Plato had written a novel.

Of course, Brandenstein, too, cannot avoid to talk on the vast amount of Atlantis hypotheses. But he stays brief on this because he has a clear objective of his own ideas before his mind's eyes.

Primarily Brandenstein talks against the "Romantics", as he calls them, who believe in an Atlantis which allegedly sank in the Atlantic 10000 years ago. Against them he puts forward the argument that in the stone age nobody would have known of such an island and that the survey of the sea ground revealed undoubtedly that such and island never existed.

The Romantics had a lack of imagination and empathy to realize the problems; instead they enjoyed in the exuberantly growth of their own phantasies.

Both Romantics as well as Skeptics are confronted with the reproach that they "boldly slurred" over the fact that localization of the Atlantis island has to be understood in the context of the time, so that it must be an interpretational mistake from Solon's resp. Plato's time.

To conclude that there was no Atlantis at all if there was no Atlantis in the Atlantic is not compelling for him. This would be as if Columbus had concluded that there was no India if there was no India in the Atlantic.

Against Skeptics, he puts forward the argument that it is "completely unacceptable" to believe that Plato just invented the origin of his Atlantis account. Brandenstein emphasizes "that Plato attached great importance to find belief with his Atlantis account, and that he in no way wanted to tell inventions 'with a smiling seriousness'".

Localizations in the western Mediterranean are excluded by Brandenstein. The Spain hypothesis was refuted by Hans Herter, already. Generally, there were no sea powers in the west before the Carthaginians and Etruscans.

Before Brandensteins turns to his own try to localize Atlantis, he tries to provide interpretations for the key issues of the Atlantis account. So far, Brandenstein could serve with good and strong arguments. But now, Brandenstein's argumentation begins to weaken.

As already seen, Brandenstein considers the chain of transmission described in the Atlantis account itself to be true, because its invention would not have fit into the time, and because Plato could fulfill his intentions with the Atlantis account only if it is true.

Brandenstein believes that Solon errorneously linked two separate accounts to one: From Egypt he had knowledge on the Sea Peoples wars, from Athens he had traditions on the confrontation of Crete and Athens, as they are indeed documented in known myths. With this Brandenstein believed that only a part of the Atlantis tradition came from Egypt.

Brandenstein traces back the 9000 years mentioned in the Atlantis account to the Iranian chronology. In the context of the Iranian teaching of the 'world year' he concludes that the Atlantis war happened later. A documentation for the Iranian chronology is seen by Brandenstein in the fact that Plato's Academy allegedly was visited by an Iranian priest.

Much better documented are Brandenstein's considerations on the place of the Atlantis war in the Mycenaean chronology. By this he limits the date between 1700 BC and the Trojan War around 1200 BC.

According to Brandenstein the almost incredible sizes of the island and its buildings are due to the literary genre: A legend typically tends to exaggerations. Furthermore, the size of the island reflected its military power.

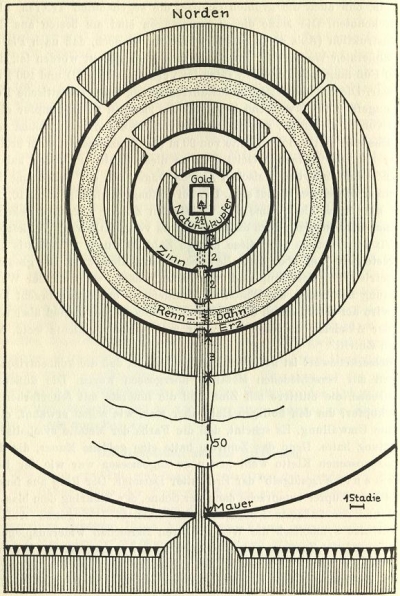

Plato got the idea that the island of Atlantis was in the Atlantic from the knowledge of his time. The original Atlantis account could not have talked of the Atlantic since it was outside of the world, known then. Rather, there is only one island which was a sea power and at the margins of the then known world: Crete.

On the hypothesis that Crete was Atlantis Brandenstein says many considerable things, yet generally his argumentation shows more and more gaps resp. tends towards speculations. Since the Crete hypothesis became questionable due to recent research we do not want to talk more on Brandenstein's theses.

One thing remains: A scientist with relevant expertise has presented a sophisticated argumentation which views the Atlantis account as a historical tradition and rejects the idea of an invention by Plato.

That the very same scientist as many others – we think of Spyridon Marinatos, John V. Luce or Eberhard Zangger – failed to offer a concrete localization of Atlantis does not reduce this merit.

[1] Studien zur Srachwissenschaft und Kulturkunde – Gedenkschrift für Wilhelm Brandenstein. Innsbruck 1968; http://titus.uni-frankfurt.de/personal/galeria/brandens.htm

[2] Wilhelm Brandenstein: Atlantis. 1951.

[3] Wilhelm Brandenstein: Atlantis. 1951.

Brandenstein (1951): Wilhelm Brandenstein, Atlantis – Größe und Untergang eines geheimnisvollen Inselreiches, Issue 3 of the series: Arbeiten aus dem Institut für allgemeine und vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft Graz, edited by Wilhelm Brandenstein, published by Gerold & Co., Vienna 1951.

Luce (1978): John V. Luce, The Literary Perspective – The Sources and Literary Form of Plato's Atlantis Narrative, in: Edwin S. Ramage (ed.), Atlantis – Fact or Ficton?, Indiana University Press, Bloomington/London 1978; pp. 49-78.

Marinatos (1950/1971): Spyridon Marinatos, On the Legend of Atlantis, 1950; in: General Direction of Antiquities and Restoration (ed.), Some Words about the legend of Atlantis by Sp. Marinatos, series: Archaiologicon Deltion, Vol. 12, Athens 1971.

Zangger (1992): Eberhard Zangger, The Flood from Heaven – Deciphering the Atlantis Legend, Sidgwick & Jackson, London 1992.