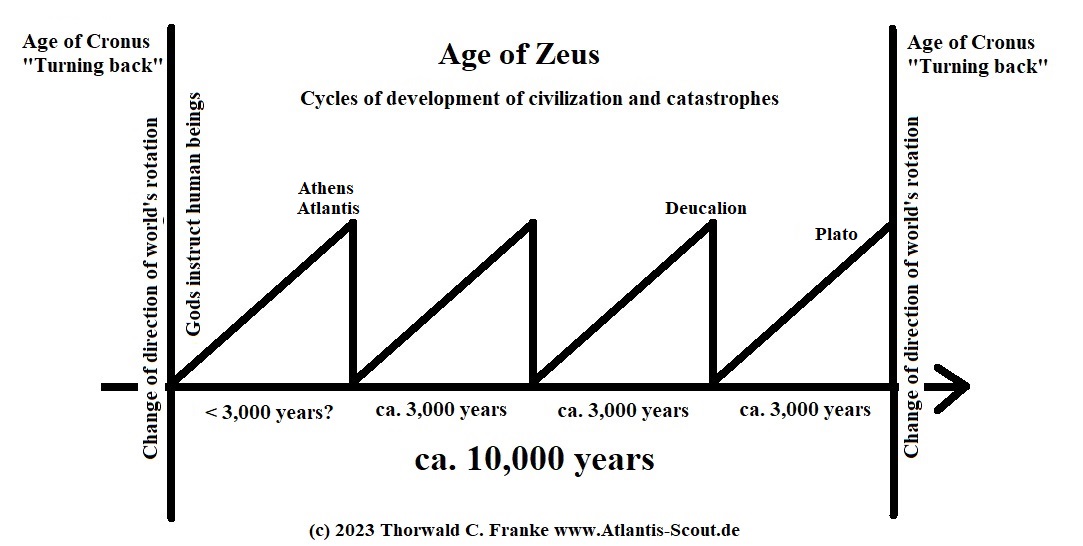

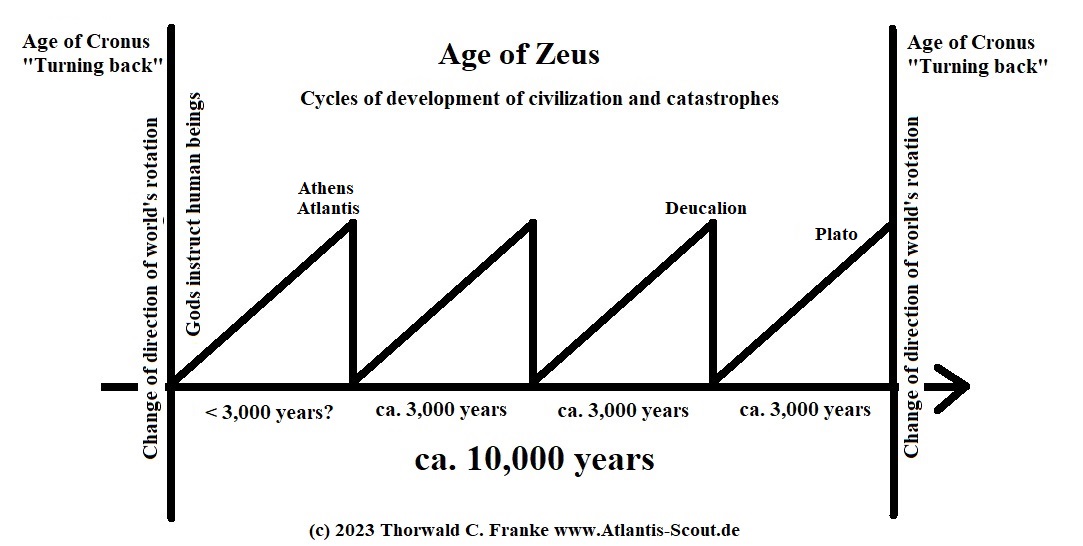

Figure: Plato's cyclical catastrophism

George Harvey PhD is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the Indiana University Southeast in New Albany, Indiana, USA. His interests span from Plato and Ancient Greek Philosophy over Metaphysics and Epistemology to Medieval Philosophy. In recent years, he has published three articles about the relation of Plato's political philosophy and Plato's cyclical catastrophism. Taking Plato's cyclical catastrophism seriously leads to valuable questions around Plato's Atlantis. But also several mistakes have to be reported, some of them quite typical mistakes in the context of Plato's Atlantis.

In the center of Harvey's considerations is the observation that the age of Cronos as described in Plato's Politicus, and shortly mentioned in The Laws, shows similarities to Plato's political philosophy, here especially pointed out for The Laws. This is of course correct, as it is said explicitly in the Politicus, that this is the purpose of this Platonic Myth (e.g. Politicus 275bc). In this connection, Harvey makes a lot of correct observations. Among them is the problem how the amenities of the age of Cronus and the harsh conditions of pre-political life fit together. George Harvey: "In order to see this connection, one must revise one’s preconceptions about what life might look like when governed by reason, from either a divine source or human legislation. Such a revision represents in my view a major teaching of the Laws." (Harvey (2018) p. 307)

Harvey also expresses the idea that Plato's cyclical catastrophism with repeated extinctions of civilizations has been established by god respectively the gods, because this is the best of all possible worlds (Harvey (2020) pp. 173 f.; Harvey (2023) aop p. 20). This basic idea is very correct, too.

Furthermore, it is an excellent idea to extract the message of Plato's Atlantis story from the comparison of the two described cities, primeval Athens and Atlantis. Yes, both cities are on equal footing at the beginnig of time. And yes, it is the job of the legislator to create a constitution under which human beings can govern themselves, given the circumstances. And yes, the gods desire the well-being of human beings, yet human freedom prevents the gods from achieving it with perfection and for eternity.(Harvey (2023) pp. 11, 16, 18)

George Harvey is at least convinced that the inquiries of the Athenian in The Laws into the prehistorical past show indeed an interest about what really happened in prehistory beyond mere myths, and George Harvey presents a series of very good arguments to underpin this claim. He also clearly notes that "the account of cyclical disasters in the Timaeus, with which Plato’s readers would have been familiar, ... is presented as a matter of recorded history." (George Harvey (2018) p. 312) – For the reader, the question arises whether this does imply a serious historical interest on behalf of Plato in real history, including primeval Athens and Atlantis? It very much sounds like this.

In his third article, the article about Plato's Atlantis story, Harvey adds a footnote in which he says that he "will have nothing to contribute to debates about the status of the myth either as a work of fiction, historiography, or some combination of the two." The neutrality of this statement shows a strange reluctance to make the usual statement that Plato's Atlantis story is "of course" nothing more than pure fiction. But it would not be fair to read too much in this footnote, since Harvey presents a list of Atlantis sceptics in this footnote, without mentioning any Atlantis supporter like e.g. John V. Luce.(Harvey (2023) aop p. 1 footnote 1)

Though George Harvey has a very sound approach and very sound basic theses, he is victim to a central error which haunts the whole analysis in all three articles, and which makes it sometimes difficult for the reader to sort out correct and erroneous conclusions. Harvey did not carefully distinguish the two types of cycles as described by Plato, but brushes over this difference (Harvey (2020) pp. 157, 168), focussing only on the simple fact that there are cycles of repeating catastrophic events. And thus, he has also not seen that the two types of cycles are nested. First, there are the repeating changes of the direction of the rotation of the world, repeating every ca. 10.000 years, and secondly, there are repeating floods and fires, repeating every ca. 3.000 years. So, there are several "small" cycles within one "big" cycle. The figures are not to be understood precisely. Egypt was thought to be older than 11,000 years at the time.

Overlooking this, Harvey made several subsequent mistakes.

First, he has not realized that the age of Cronus is not the time at the beginning of the development of civilization, where human beings still live under primitive conditions. The time at the beginning of civilization is rather in the age of Zeus, when either the gods establish first human beings directly after the most recent change of the direction of the rotation of the world, or after each following "small" catastrophe, when human beings have to develop civilization again without the help of the gods. There are similarities to the age of Cronus, yes, but it is the age of Zeus. Harvey himself realized that the behaviour of Athena corresponds rather to the age of Zeus, not to the age of Cronus, when she leaves the Athenians alone after a time of divine preparation; and also Poseidon acts like this (Harvey (2023) aop p. 7). It is well-observed that Poseidon is the son of Cronus and that his way of preparing human beings for being left without divine guidance shows similarities with the age of Cronus (Harvey (2023) aop p. 2), but it is not the age of Cronus.

Then, Harvey does not realize that the "small" catastrophes are meant as regional catastrophes, while only the change in the direction of the rotation of the world is indeed a "big" and worldwide catastrophe. For Harvey, all these catastrophes are worldwide catastrophes. Harvey is right that Plato is not fully logical, considering that regional catastrophes do not require a subsequent standalone development of civilization because there are surviving civilizations in the neighbourhood to learn from (Harvey (2018) S. 311). But maybe this is a modern view, and Plato for his time did not think of cultural exchange as we do in our time. Before the age of discoveries in the 15th century, most world civilizations developed on their own, separated by seas.

More severe is the subsequent error to believe in very long times of the development of civilization. Harvey interprets the phrase "myriakis myria" as "thousands upon thousands of years" (Harvey (2020) p. 162) He has not seen that it is literally "ten thousands time then thousands", and that 10.000 is the length of one "big" cycle. Therefore, "myriakis myria" points to many times repeated developments. Granted, the passage sounds as if the development of civilization takes millions of years, but when realizing that the focus of the speaker is on the "big" cycles only, the perspective becomes clear. Therefore, it is not true that human beings live in primitive conditions for most of the time as Harvey assumes. They reach the height of the ideal state only shortly before the next catastrophe, and the development of civilization follows a linear growth, not an exponential growth. Exponential growth is indeed what happens in reality, but it is at the same time a very modern idea. Plato did not think like this.

It is strange that Harvey overlooked the reason given in the Politicus for the "big" cycles: Once the gods leave the world alone, it starts to deviate from its course, and in order to avoid its complete deterioration and to keep it running for eternity, the gods have to "turn it back", like a clockwork (Politicus 273b-e). This is still in harmony with the reason given by Harvey, that the gods want to shape the best of all possible worlds with as much virtue in the cosmos as possible, but not as intended by Harvey: For Harvey, it is about a kind of mathematical optimization of the amount of virtue, summed up over the primitive and the civilized times (Harvey (2020) pp. 173 f.). In primitive times, there are few people over a long time with neither extremely good nor extremely bad characters, in civilized times the opposite, and both is needed supplementing each other, especially considering Plato's idea of reincarnation (Harvey (2020) pp. 170-172).

It is not fully clear how this optimizes virtue in the cosmos and thus is not very convincing. Furthermore, Harvey's approach builds one conclusion upon the other, thus reaching opinions which can hardly be considered Plato's opinions, because we do not know whether Plato would have drawn and accepted all these conclusions. And a chain of conclusions building on one another is always in danger of deviating from the target, the more so the longer it is, since small misunderstandings can thus multiply to very big misunderstandings.

The true reason for cyclical catastrophism is better clarified by the traditional explanation, that Plato's gods are limited in their power over the cosmos, and this is even more true with respect to the "small" catastrophes. Furthermore, the deviation of human beings from virtue is also beyond the power of the gods, who want to respect the free will of human beings. This results in "catastrophes" like the possible breakdown of an ideal state over time without a natural disaster. But for Harvey the gods, at least in The Laws, are not limited in their power (Harvey (2020) p. 172). We cannot support this.

Also not correct is that the cycles of repeating catastrophes are not regular (Harvey (2018) p. 311). But for Plato, the "small" catastrophes are effected by the courses of celestial bodies which are the hallmark of regularity in Plato's world view, though maybe not with full perfection. It is not clear whether it is allowed to impute such a thought to Plato, but from a modern point of view it may happen that several such cycles overlap and thus form a pattern which does not look regular in the short term. But in the long term, also such a more complicated pattern repeats.

It is questionable why George Harvey always talks of the "myth" of Atlantis. As he himself says, the Athenian in The Laws considers the stories of the past as "importantly different from the passages whose mythical status is uncontroversial" (Harvery (2018) p. 312). Following this logic, the Atlantis story is not a myth. (Besides the fact, that the Atlantis story is not presented as a myth, and still does not become a myth in case Plato invented it all. It may be called a Platonic Myth, but this is not the same as a myth.)

About primeval Athens it is said: "The result is a city that almost exactly matches Socrates’ description from the previous day" (Harvey (2023) aop p. 8). It turns out that Harvey has overlooked that Critias is supplementing the historical tradition to the full ideal state (Timaeus 26cd). Therefore, primeval Athens in the Critias is of course exactly the ideal state, while the historical tradition comes only close to it. This is at least the plot of the Atlantis dialogues.

According to Harvey, the Athenians are not descendants of gods and get knowledge from goddess Athena so that they can establish the appropriate constituion by themselves (Harvey (2023) aop pp. 5, 8) But this is not fully correct. Also the traditional kings of Athens are desendants from gods, and goddess Athena does not only provide wisdom and knowledge but also the constitutional order (Critias 109d: ἐπὶ νοῦν ἔθεσαν τὴν τῆς πολιτείας τάξιν). Harvey's view of the Athenians is slightly too modern. Projecting too modern views into the past is not allowed. Nevertheless, Harvey is correct that it is all about being prepared for being left alone by the goddess, and having no need of divine descent as the Atlanteans have.

Harvey wants to protect god Poseidon from being responsible for the bad performance of Atlantis in comparison with primeval Athens. It is not allowed, says Harvey, to say that Poseidon failed to establish a good constitution, corresponding to the role of the gods according to the cosmology of Timaeus. Furthermore, Harvey says that "Critias’ attitude appears to be that we humans are in no position to judge the conduct of one god as better or worse than another." (Harvey (2023) aop pp. 16, 13) But in Timaeus 42e we read of "the best possible guidance they [the gods] can give", and this means that Poseidon tried but could not do it better. He is clearly not as good as Athena in providing a wise constitution to human beings, and it is not true that Critias forbids such a judgement. Quite the contrary, the message of the Atlantis story can only be understood when making such a judgement. And it does not make sense to blame the free will of the human Atlanteans for the mess (Harvey (2023) aop p. 16), since the Athenians did not better than the Atlanteans by their own free choice, but by Athena's choice.

It is not correct that the productivity of Atlantis even verges on the absurd (Harvey (2023) aop p. 6 and footnote 7). In truth, also the Atlanteans have to do farming, as the Athenians have to do, and they even have to build irrigation canals to survive the drought in summer, and no dessert is growing on trees in Atlantis. The latter may be a mistake based on Benjamin Jowett's translation: "... and the pleasant kinds of dessert, with which we console ourselves after dinner". Other translators have it better.

It is wrong that the Atlantean kings meet "every five or six years" (Harvey (2023) aop p. 9). In truth, they meet "in" the fifth or "in" the sixth year, which means in modern language that they meet every four or five years. Quite a common mistake.

It is assumed that both cities, primeval Athens and Atlantis, suffered their downfall at the very same time (Harvey (2023) aop p. 19), but this is doubtful. Since the catastrophes were regional catastrophes, their downfall happened most likely not at the same time. [PS 19 March 2023: Harvey is correct. Both catastrophes happened most likely at the same time. There are several reasons underpinning this assumption.]

Harvey observed that "the gods ... spurred Atlantis into aggression so that its defeat would bring it back into harmony" (Harvey (2023) aop p. 21). But precisely spoken, it was Poseidon only, not the gods. And taken even more precisely, this is a contradiction to Plato's own concept of the gods, who are considered completely good and never advising to do bad. The role played by Poseidon is not completely understood by Harvey nor by any other researcher. An open question.

Finally, Harvey speculates that since we do not see what led to primeval Athens' victory, it may be, that Athens' victory came about only due to external factors (Harvey (2023) aop p. 21). This is another idea which is quite un-Platonic. It may be that the Athenians were wise enough to calculate on external factors, e.g. waiting for a good opportunity for action brought about by external factors, but this would still be their own merit, not the opportunity's merit.

Harvey (2018): George Harvey, Before and After Politics in Plato’s Laws, in: Ancient Philosophy No. 38 (2018); pp. 305-332.

Harvey (2020): George Harvey, The Cosmic Purpose of Natural Disasters in Plato’s Laws, in: Ancient Philosophy No. 40 (2020); pp. 157-177.

Harvey (2023): George Harvey, Divine Agency and Politics in Plato’s Myth of Atlantis, in: Apeiron, ahead-of-print online 03 March 2023; aop pp. 1-22. aop = ahead-of-print pagination.